Inside Amy’s Place, a Drug Recovery Sanctuary for Young Women – VICE UK

Two years ago, in Los Cabos, Mexico, I experienced a brief taste of extreme wealth. Ten hazy days of tropical opulence, stilettos sinking into the sand, Cuban cigar ash in the jacuzzi and dinner parties in black-tie, all of which was kindly paid for by my then-boyfriend’s dad.

On the seventh day, I discovered that the local pharmacies sold over-the-counter Xanax. Despite projecting an outward display of decadence at the time, I felt profoundly empty, and was so relieved that I could finally slip into a state of dazed unawareness. I didn’t appreciate reality, or want it, no matter how luxurious.

I was 17 years old then, and can only understand the absolute tragedy of this period of my life because of my current circumstances: where I live, and how different I feel today. Most young women facing addiction problems do not get the chance to explain what happened and why it happened.

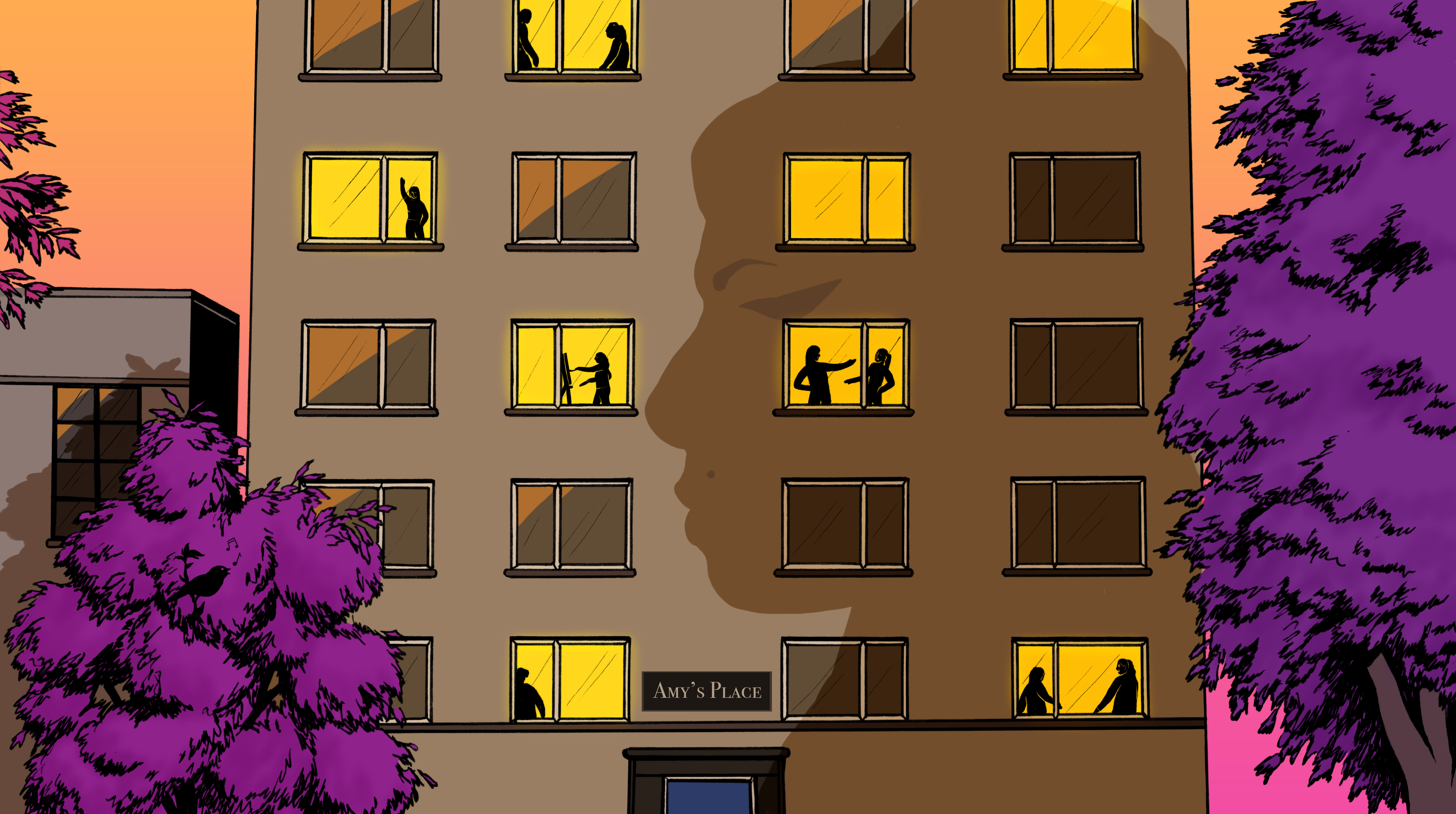

I am one of only 13 lucky ladies residing at Amy’s Place, a stack of flats in east London that provide an oasis for young women in recovery from drug addiction. Many of the girls living here would otherwise be lying in a doorway unconscious, or on a mattress beneath a bridge.

Sometimes, I just stand across the street, in the rain, and look up at Amy’s in wonder, at our matchbox building and all its glowing windows, lit up, promising homely warmth and a cosy familiarity. It’s here I have the opportunity to reflect on the trajectory my addiction has taken, as well as the addictions of the other girls living here, and how our stories are representative of a struggle many young women are undergoing around the world, in our search for meaning and intimacy.

I was a curious child. Full of three-year-old enthusiasm, I’d wave at every single commuter stuck in the local 5PM traffic jam. Secondary school came as a shock: I found the meaninglessness of these lessons unbearable. When back at home, I felt alone – and because of the shame surrounding loneliness, I incorrectly felt it was a reflection of who I was.

From the age of 12, I used Instagram feverishly – it provided a wonderful illusion of intimacy and perfection. Social media was my original addiction, and I ignored the side-effects: narcissism and feeling inadequate.

I understood the marvel of simply being alive, but that just increased my self-hatred, because I knew that every single day I was squandering it. I idolised Skins: the show’s aesthetic and the glorification of unhappiness and drug abuse is so alluring. I remember, at 14, excitedly writing in a diary that I could use alcohol to take control of my emotions. That I could literally change my mood and who I presented to the world, within minutes. I fell in love with the control.

Alice in Wonderland told us that one pill makes you larger and another makes you smaller. She forgot to mention the wavy TV static of ket, the breathless carelessness of Xanax, the melting violet Vallies and the vastness within psychedelics. In my room, I’d stash DMT vapes, blister packs of valium and oxycodone, counting them out on my bed with all the joy of a child rifling through pick ‘n’ mix.

After a night walking around Brighton seafront on LSD, aged 16, I believed I’d witnessed the “true suffering” of mankind. Everyone appeared so utterly lost and devoid of hope, leering at me from doorways. For months after, strangers’ bodies seemed separated from their souls, and there was something horrible peering out at me from behind the sockets of their eyes. They had lost their identity as humans, and I felt I had too. I dealt with this by taking more Xanax, to make me stop caring completely.

At 17 I flew off to live in Australia with a boy also looking for a sense of wholeness in another person. It was that December, when we’d flown to Mexico for his dad’s second wedding, that despite having access to the supposed highlife, all I pined for was to be unconscious. Looking back, I now see I was lacking that intimacy we all crave.

My mixing of opiate pills and benzos became a frequent gamble with death. Eventually, my family could no longer be in denial about the severity of my addiction, and I received professional help at a clinic in the Netherlands for emotional dependency problems. During ten weeks of confrontation, I discovered that despite never being continually addicted to any one substance, my diagnosis as an addict was about behaviour patterns and compulsiveness. These weeks laid the necessary foundations for a new life.

Rehab is just the beginning.

The majority of people with addiction problems relapse after rehab. This is partly because, when they leave treatment, they must return to the living situations and unhealthy relationships that contributed to the drug abuse that landed them there in the first place. Young women particularly are taken advantage of while at this precarious stage in their recovery, due to stigma, abusive relationships and returning to jobs such as escorting.

This is why Amy’s Place is unique. It’s a recovery housing project created by the Amy Winehouse Foundation, in partnership with Clarion Housing, to create a safe environment for young women who need somewhere to restart their lives. It differs from most supported housing, due to its availability only to women aged between 18 and 30, a subgroup of society with a vulnerability to self-inflicted abuse.

The number of teenage girls admitted to hospital for self harm and attempted overdose has spiralled over the last decade in the UK and US. The suicide rate among young women has increased ten-fold in the US in the last decade, and is currently at its highest in the UK since 1981. This has coincided with the rise of social media on mobile phones.

Studies show that social media has disastrous impacts on wellbeing, particularly when it comes to creating anxiety among teenage girls. Anxiety and other mental health problems are interchangeably linked with addiction. Most worryingly, only 10 percent of addicted drug users will stay long-term sober.

This is why Amy’s Place can provide a solution. It is not just a home, it’s a support system, a secure place to flourish and create the woman-to-woman relationships that have given our sobriety meaning.

Upon arriving, a resident will sign a tenancy agreement to a flat, for a life-altering two-year chance to heal from trauma and rediscover hope, with gradual reintegration back to conventional society. The main requirement to apply is to be 90 days clean from substances. There are occasional drug tests, and too many positive tests can result in residents being asked to leave.

We’re given our house keys, armed with a personal key worker and must commit to attending a 10.30AM “check-in”, a time for residents to share absolutely anything and build relationships. This is mandatory for the first three months we live here, but most continue of their own will. Our key workers provide emotional and practical support, structure to our days and a 24/7 on-call system in case of an emergency.

It is not the sort of place whose residents barely mutter a tepid “hi” in the corridor. Lockdown didn’t feel so impactful, because we had each other. We frequently go out together for dinners, dancing and pond swimming, even organising our own event, a creative open mic night. The entire house is full of deeply talented women.

Claire is one of them. She’s 21, an eight-month resident originally from ketamine capital Bristol. Among hippie-patterned throws, Vagina Museum postcards and one-year-sober party bunting, she sits regally, with a blanket wrapped around her legs.

“I have this vivid memory.” Her eyes widen. “I used to have a best friend called Thaz. There was something wrong with his brother, and at five, we took his medication. Definitely a bit of an omen.”

Claire was diagnosed with scoliosis aged 11, leading to pain and isolation, and by 15 was regularly using weed and ecstasy. A tumultuous relationship with her parents meant she left the family home two years later, discovering Xanax while sofa surfing. “That’s the drug which meant I couldn’t function. I also became promiscuous and unpredictable.”

After a long trip to South America, a treasured relationship broke down. She started using crack cocaine as well as Xanax and lots of alcohol. “I would puke over the bed and watch it build up in different colours,” she says. “I used to think empty tinnies and bottles of Echo Falls were room decorations. My friends thought every time they saw me that it would be the last.”

“During my addiction, there were no Tuesdays, no Wednesdays, no birthdays, no holidays. It was just one long solid nothing. I moved around and I breathed, but I didn’t really know what was going on. I was very vulnerable in that state. There were a lot of people who took advantage of that.”

Claire’s GP diagnosed her with PTSD from violent experiences she’s had with men, and told her that unless she applied for rehab, she’d die. After completing rehab, she stayed at another recovery project for 12 months before a flat at Amy’s Place became available.

“I didn’t have a strong support network around me. I struggled to survive. I spent my time in the dark, without gas or electricity, and the support staff weren’t aware,” she explains, adding that coming to Amy’s was pivotal to her recovery.

“Now, there’s always another resident at check-in who will give me advice, or ideas about how they dealt with similar situations themselves, in a non-shameful, supportive manner. It’s completely revolutionary to just be able to text my mum, ‘Happy birthday.’

“I’m living the life that I’ve wanted. I can deal with my emotions and memories, which aren’t destructive to myself and other people. My story isn’t over. Every day I struggle with addictive behaviours that aren’t drug use, but I’m finding power in the liberating of myself, to be myself.” She takes a deep breath. “When I was in the middle of my addiction I’d go to sleep and I wouldn’t know who I’d be the next day. Now, I can wake up and I’ll still be the same person.”

In the flat below Claire is Violet. She arrived at Amy’s when she was 29, and has almost completed her two years here.

From the ages of six to 12, she watched her mother deteriorate from cancer, due to an inherited gene: “Her hair fell out from chemo, her boobs were taken off. Her skin went yellow due to liver failure. She would just sit numb, staring out of a window, which was horrific. I was with her when she died.”

Violet’s father put her in the position of a new wife – she cleaned, cooked and looked after her brother and sister, while he made sexual comments towards her.

At 12, Violet found alcohol. Three years later, she was taking a lot of MDMA, running around with wealthy north London girls until 5AM. “I’d found my tribe – these creative, intelligent people who wanted more from life,” she says.

“One of the boys would pick me up in his new Mercedes and whisk me off to a mansion in Hampstead. Suddenly I was around the sons of millionaires, who all lived inside these huge houses, paying for drugs. I was young, I was beautiful, I had all this power. My looks were my golden ticket. But that emphasised my bulimia, because I was like, ‘If I don’t look great, I’ll potentially lose my whole livelihood here.’”

At this time, her dad was at his worst: “He was throwing up outside my bedroom, being violent with all of us. There was just this weird eeriness in the house, because no one wanted to be there.”

At 18, she left, finding relief from childhood trauma in obsessive walking. “I’d just walk for six or seven hours a day – twice, I broke a bone in my foot.” She sang professionally in bars and abused painkillers, and despite sleeping on office floors completed an arts degree at Central St Martins, graduating with one mark off a first. When she inherited £50,000 from an aunt, she bought herself a houseboat, which she filled with lots of beautiful things. But, she says, one day she left the tap running, before passing out drunk elsewhere. When she came back, the boat had sunk.

Even when Violet came to Amy’s place, she admits she didn’t truly accept she was an addict. “I came here in the hope to stay sober and get housed – I was just like, ‘Yeah, everyone does drugs.’ Only after I overdosed on medication, 14 months into my stay, did I take recovery seriously.”

Being able to create a long sought after home at Amy’s has vastly improved Violet’s psychological health: “I can unfurl,” she says. “For me to have enough physical space, that has been probably the most important part. Something that I’d never found possible anywhere else.”

In Violet’s latest painting, sullen pinks and baby blues depict a muse floating in a pool. “That is probably a projection of where I am right now, this serenity,” she says. “I’ve blossomed. I’m doing a Masters degree, I’ve learnt to mother myself, I’ve found my family in my friends. This place has saved me, which is a fucking miracle. The Winehouses lost Amy, but now they’re saving people’s lives.”

She’s right. Despite how composed we and the other residents might first seem, we’ve all been near death. There are hundreds of ghosts who could be walking where we walk, sleeping in the beds we sleep in. Yet it’s Violet, Claire and myself – and the other residents, past and present – who are the lucky ones. In the three years since opening, 40-odd girls have had the chance to pass through Amy’s. But the waiting list is full, and there are countless young women leaving treatment every day, vulnerable and afraid.

I am almost a year into recovery now, and want to dedicate my life to writing, to raise awareness of how our increasingly dystopian society – and the denial of it – is having such a drastic impact on people’s spiritual, psychological and physical health.

In this country, we enable each other, convince each other that our segregated living styles and use of substitutes – food, drugs, television, social media – for intimacy is normal. The consequences of this normalisation are reflected in those shocking mental health statistics I mentioned earlier.

Addiction itself is all in the intention. It doesn’t only manifest in drugs, it’s a many-faceted, compulsive substitution for human intimacy and emotional security. I didn’t previously have the awareness to know any better, nor the strength to change my behaviour, and these two obstacles apply time and time again in all the diverse stories of addiction I encounter. With the aid of my 12-step sponsor, I have been taught how to be a person without the need for drugs – and being at Amy’s has empowered me to do this.

This mindset I had – always trying to escape – meant I was missing the only moment we have: the present. Western culture mocks spiritual awareness, and it’s deeply sad that at one point I believed humanity was restricted to a lonely, isolated rock drifting through space, going nowhere, with no real purpose. I now feel we are all divine; that the idea we are individual, that there is a “self”, is a fiction created by the ego, and even the spider scaring me to tears at night is a part of me, albeit not my favourite part.

These days, it is in pond swimming that I find serenity. Sinking beneath tranquil waters, under the grey sky, it’s a cold shock into the here and now.

The starkness of the icy water gives clarity to the mind, and is the perfect antidote to feelings of being dissociated from my own body – the greatest cure for my detachment from the world.

Upon emerging each time, I remember that this reality can be undoubtedly beautiful, if only I continue to choose it.

Some names and places have been changed to protect the anonymity of interviewees.

Read Liza’s website about addiction and other subjects here.