DIY Drinking: House-made ingredients are raising the bar – The Portland Phoenix

|

“When I moved to Boston,” UpStairs on the Square bar manager Augusto Lino explains, “it was uncommon for bars to have anything house-made beyond a large container of vodka filled with pineapple on the back bar. Eastern Standard wasn’t open yet, the B-Side was in a residential neighborhood, the bar at No. 9 Park was inside a fine-dining restaurant — you had to look hard.”

Lucky for us lushes, times have certainly changed.

A love of the homegrown and homespun — the slightly lopsided bread, the wonky-looking salumi dry-aging in the garage, the misshapen vegetables plucked from a backyard patch — is an undisputed part of the current culinary zeitgeist, having made its way into the mainstream on the coattails of the farm-to-table movement. While the idea is by no means new, its renaissance has resulted in a surge in creativity for culinarians across the board.

The bar, formerly a bastion of consistency, is no exception. We got behind the stick of some of Boston’s top watering holes to get a glimpse of the personal touches that continue to advance the game.

|

BITTERS, ESSENCES

One glance at the shelves of a place like Somerville’s Boston Shaker is proof there’s no shortage of independent bitters producers on today’s market, from Bittermens to Scrappy’s to the Bitter Truth. It’s easier than ever for bartenders and novice cocktail enthusiasts alike to get their hands on exotic flavors — sarsaparilla bitters, lavender bitters, juniper bitters, you name it. So why bother with an in-house bitters program?

“You’re going to get a lot of people who don’t give a shit that you make your own bitters, let alone know what bitters are,” says Russell House Tavern bar manager Sam Gabrielli, who has been experimenting with his own bitters batches for about a year and a half. “I could probably have just as much of an effect as a bartender if I wasn’t taking the time to make these, but if that’s really what gets your goat, then why not? I like having ownership over my product. If I could put a still in my basement, I would.”

Gabrielli counts himself as a casual hobbyist when it comes to his homemade ingredients. Most of the time, he’s perfectly happy to use what’s already on the market. “I could try to make Angostura bitters,” he says, “but I’m never going to, because they’re already great.” When he does take the time to whip up something personalized, though, the flavor profiles are off the charts. His orange bitters are pithier and spicier than many mainstream labels. His peach-anise bitters, which he shares with the drink wizards at Union Square’s backbar, are reminiscent of a heady late-summer afternoon in a peach orchard.

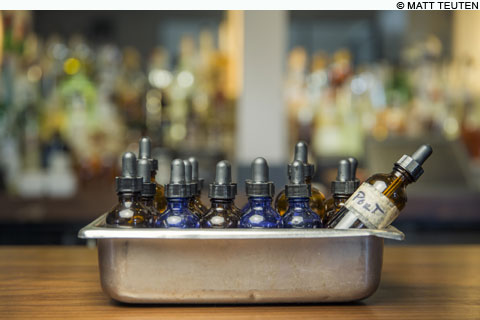

Across the river at Clio, bar manager Todd Maul — often hailed as the brilliantly mad scientist of the Boston cocktail scene — is eschewing a traditional bitters program in favor of something a little more elaborate. At his bar, he plunks down a tub packed with glass eyedropper bottles with a flourish. “Essences,” he says with a grin. I peer at a few of the scribbled labels as he begins to unload them: port, blond Lillet, Middle Eastern black lime, Cuban cigar, yam.

“We wanted to find something that doesn’t exist,” he says, squeezing a tiny drop of black-lime essence onto my finger. After I taste the essence, a sip of dry Curaçao becomes something much more; the orange notes are spiky, lighting up the whole back of my tongue.

Through the use of a rotary evaporater, or a rotavap, Maul and his team separate spirits (and anything else they can think of) into their base-level compounds, concentrating one element of the flavor profile into an extract. The goal is to use the essences like “vermouth on steroids,” rounding off edges or creating sharp points in a drink’s profile without overwhelming a spirit’s original flavor.

“It just seemed like a better way to approach how the alcohol is actually talking to us,” he explains. “You go to a chef because you like his palate, right? Every bartender should have a very distinct palate. We can make a drink that speaks to the way we see it, and the way we want to present it. It’s the reason why there’s a Jimi Hendrix and a Muddy Waters. It’s the same instrument; they just play it very differently.”