Fidel Castro’s Fateful Visit to New York, 60 Years On – Americas Quarterly

When Fidel Castro arrived in New York to address the UN General Assembly in September 1960 he was a minor player on the world stage, the head of a Caribbean nation who had been in power barely 18 months.

By the time he left just a week and a half later, everyone knew his face. He had forged alliances with some of the most important leaders in the developing world, expertly positioned himself as the maverick ally of the United States’ downtrodden African-American population, and most crucially of all, befriended Nikita Khrushchev and laid the foundations for a long and fruitful relationship with the Soviet Union.

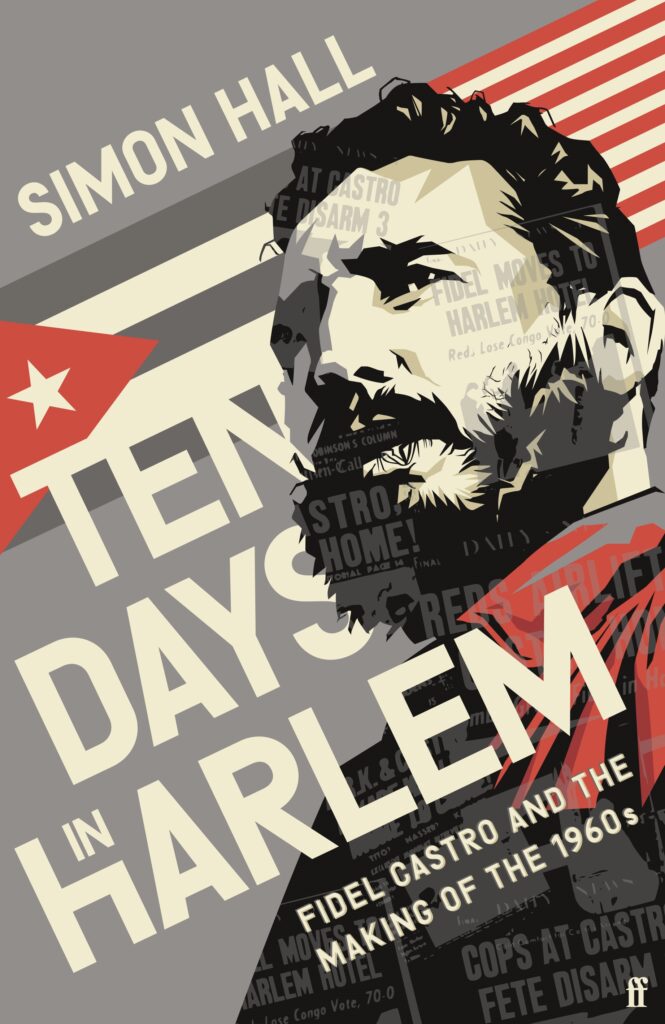

Simon Hall’s Ten Days in Harlem: Fidel Castro and the Making of the 1960s tells the story of a riotous and remarkable short period in which the Cuban leader firmly planted the flag of the Cuban revolution on the geopolitical map.

It was, Hall writes in his well-researched book, compelling, entertaining and at times scarcely believable: “The trip put the Cuban leader on the world stage, confirming his international standing and strengthening his own commitment to lead the global struggle against imperialism. For the Americans, his antics, as well as the contents of his speech before the General Assembly, confirmed their belief that he had to go.”

When Castro touched down in New York in the late summer of 1960, the world was in flux and that was particularly true for the nations outside the immediate orbit of the two superpowers. The non-aligned nations, countries like India, Indonesia, and large parts of the African continent that were enthusiastically throwing off the shackles of colonialism, were trying to find a role for themselves.

Like playground bullies urging the weaker kids to take sides, the United States and the Soviet Union used coercion, threats, sweet trade deals and sweet talking to bring them under their influence.

Cuba was already heading inexorably towards the Soviet sphere before Castro arrived in Manhattan. Hall’s readable book tells how his late summer sojourn hastened that move.

Appearing at the UN offered the Cuban leader a rare platform of legitimacy and he took advantage. Inside the hall, Fidel, resplendent in the olive drab fatigues he wore throughout the trip, spoke for four hours and 29 minutes – still a record for the General Assembly – and railed against imperialism, colonialism, capitalism and a few other -isms to boot.

But it was outside the famous UN building that he made a greater impact.

The U.S. had forbidden the Cubans to leave Manhattan and the manager of their hotel refused to fly a Cuban flag outside and banned them from eating in the hotel dining room. The Cubans were outraged. After first threatening to sleep on the sofas and lawns of the UN compound, they packed their bags and moved the entire delegation to the Hotel Theresa in Harlem.

It was a brilliant publicity coup. Not only did it bring Castro attention as a maverick in a sea of suits, the location, slap bang in the heart of one of Black America’s most famous neighbourhoods, allowed him to shine a global spotlight on the United States’ racial problems. By hammering home the inequalities evident in and around Harlem, Castro was able to portray himself as the voice of the downtrodden and the disadvantaged, a message that was particularly resonant in Africa, where anti-imperialist independence movements were in full swing. Almost overnight, the little-known leader became an important reference point for other non-aligned nations.

Ten Days in Harlem: Fidel Castro and the Making of the 1960s

by Simon Hall

Faber & Faber

Hardcover, 288 pages

September 8, 2020

World leaders headed uptown to sit in Castro’s dishevelled suite at the Theresa. Surrounded by discarded cigar butts and dirty laundry, he met with many of the iconic personalities of the moment: Malcom X, Allen Ginsberg, Khrushchev, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and Indian leader Jawaharlal Nehru.

Day and night, the sidewalks outside the Theresa were filled with supporters and opponents. Bands played, sympathizers turned up to deliver El Comandante home-cooked food, and others threw rotten eggs into the pro-Cuba crowd. Castro, smug in the knowledge that the world was watching his every move, lapped up the attention.

Hall’s book may not provide much new material for serious Latin American scholars – it sometimes reads too much like a collection of quotes from speeches and newspaper archives – but it is an interesting portrayal of a fiery and transformative time in Cold War history and rich in detail.

The story of Castro’s UN visit is essentially an explanation of the end of the beginning, the period in which the United States and Cuba, still seething after Castro’s overthrow of dictator Fulgencio Batista in January 1959, went from estrangement to antagonism to outright hostility.

Mutual mistrust was evident long before his trip to the UN, but the enmity shown by both sides on such a major stage confirmed the relationship was beyond repair.

The first thing a triumphant Castro did when he returned to Cuba was give another bellicose speech to 150,000 of his compatriots. Days later, the US imposed a trade embargo that would last more than half a century. Diplomatic relations with the island were severed in January 1961 and in April came the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion. Castro, who prompted much of the fury by nationalizing US businesses and property, ended any chance of détente by formally declaring Cuba a socialist state on May 1.

This prologue to the long-running feud is an informative and rollicking read right up to the very end, when the Cubans boarded their Cubana Airlines plane to return to Havana only to be confronted by US marshals, who impounded the aircraft, claiming monies were owed to American creditors.

The Cubans were loaned a smaller Soviet Ilyushin a few hours later, but several of them were forced to spend the night on the tarmac, wrapped up in blankets to protect themselves from the cold. The Cubana plane was released the next day and the rest of the delegation flew home. But the needless stunt was indicative of how American intransigence pushed the Cubans towards the East. As he boarded his plane home, Castro declared in English, “The Soviets are our friends. Here you took our planes… Soviets gave us plane.”

__

Downie has lived and worked in Latin America for almost 30 years, reporting from more than a dozen countries, including Cuba. He is the author of Doctor Sócrates: Footballer, Philosopher, Legend, a biography of the Brazilian footballer and political activist. He currently divides his time between the UK and Brazil.

Tags: Cuba, Fidel Castro, United Nations General Assembly