How Che Guevara’s iconic image became a design classic – RTE.ie

Opinion: the enduring appeal of the revolutionary’s iconic image suggests that style matters even in military conflict

By Jane Tynan, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

In 2017, An Post issued a one-Euro stamp bearing the graphic image of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death. Designed by graphic design agency Red&Grey, the stamp is based on an artwork by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick.

The 1959 Cuban revolution, led by Fidel Castro, brought about the transformation of Cuba’s society. Cultural exchange through literature, images, film and art brought the revolution to the world. This image of Guevara spread rapidly following his assassination in Bolivia in 1967.

The famous ‘Che’ photograph, entitled Guerrillero Heroico, was taken by Alberto Korda at a funeral in Havana in 1960. Korda took the photograph while working as a photojournalist for the government newspaper Revolución, but was not published due to its poor quality. Korda then gave Italian editor Giangiacomo Feltrinelli the photograph and, having obtained the exclusive rights to Guevara’s Bolivian Diary following his death in 1967, put the image on the cover.

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From LibEnt Music, trailer for Kordavision, a documentary about Alberto Diaz Gutierrez Korda, the photographer who shot the iconic portrait of Che Guevara

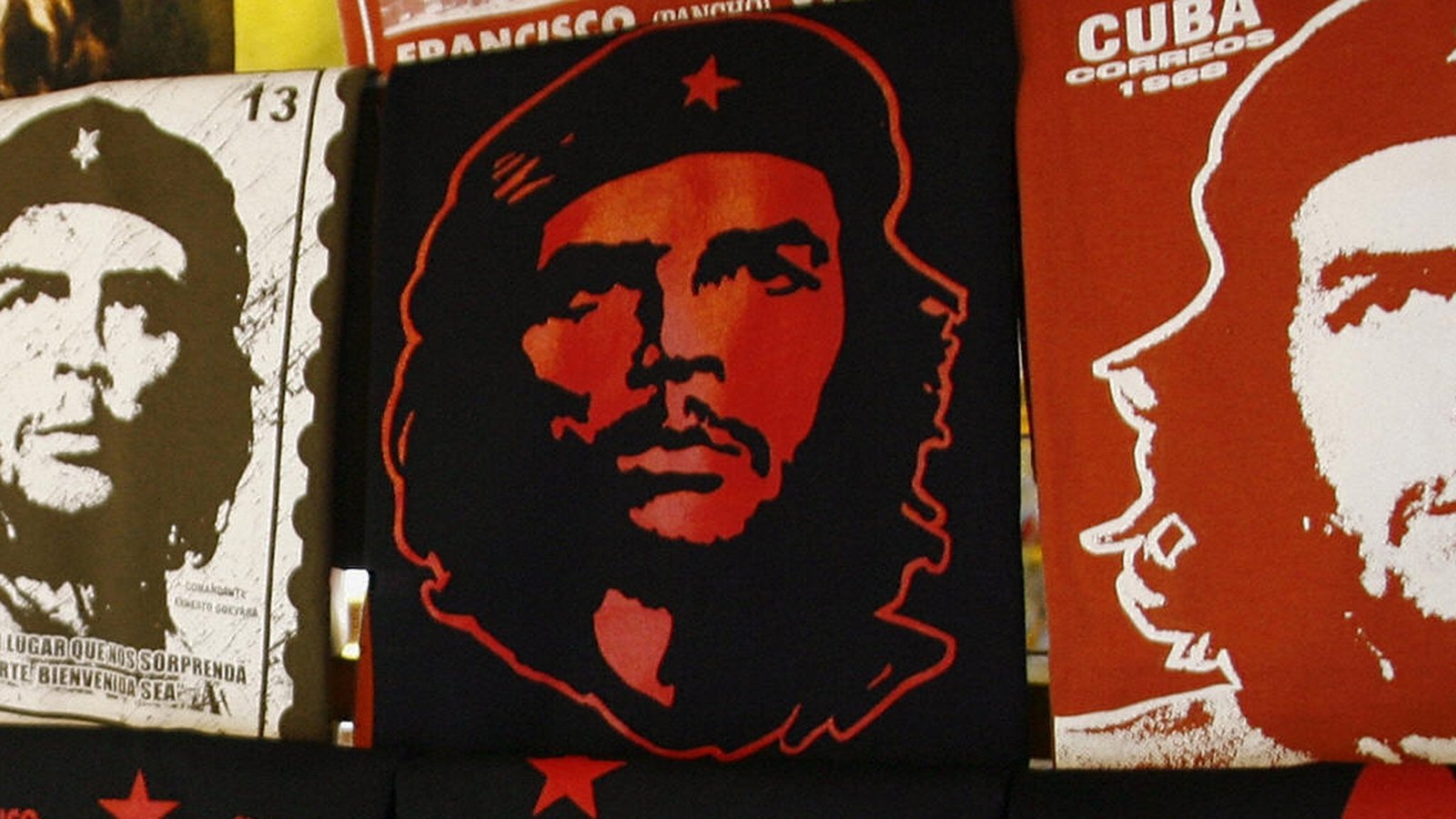

Fitzpatrick discovered the Korda photograph – conflicting accounts suggest he might have got it from Dutch anarchist group Provo or from the German magazine Stern – and used it to create a black and red screen-printed poster soon after Guevara’s death. This version was reproduced widely and gave the ‘Che’ image universal appeal as a symbol of revolutionary heroism. Heroic Guerrilla was the incarnation that gave the image currency, a co-creation emerging from various connections within radical European circles at the time.

Images were a powerful force in garnering international support for a revolutionary Cuba. Photographs that created the image of the revolution were circulated in newspapers, in touring exhibitions and were later re-purposed by graphic artists. The ‘Che’ image inspired protest movements, became a rallying symbol for Marxist groups and was re-purposed to sell all manner of commodities.

By the end of the 20th century, the Guevara image was not only powerful, but also very marketable. The Che Guevara T-shirt, for instance, which began as a countercultural statement was later sold as a fashion item. Undoubtedly, many wore the t-shirt with only a vague notion of who he was.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Six One News, 2017 report on An Post’s issue of a stamp featuring Che Guevara

One of the curious aspects to the ‘Che’ image was its transnational appeal. The photograph, and the graphic image it spawned, came about through Guevara’s creativity in how he presented himself as a revolutionary figure, one of a cast of characters who, partly by accident, partly by design, created an attractive, dynamic image that brought the Cuban revolution to the world.

Revolutionary images were not fictions, though, but are rooted in the events of 1953 to 1959, whereby guerrilla warfare demanded flexible, informal and unauthorised military methods. If creativity was a feature of guerrilla warfare, it was also at work in fashioning the irregular appearance of the rebels.

Cuban rebels – both men and women – wore field caps, berets, fatigues, and various clothing styles; combining civilian and military clothing often made combatants indistinguishable from civilians. Male bravado distinguished the rebel leadership whose cowboy hats, long hair and cigar-smoking are by now well known.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, Mark Little reports for RTÉ News from Havana in 1997 on the state funeral for Che Guevara 30 years after his death in Bolivia

In Norberto Fuentes’ biography of Castro, the leader of the revolution jokes that Guevara “was scruffy because he thought that was the poster child for rebellion to the extreme”. But Castro goes on to admit that the improvised look grew on him: “I must admit, in the end Che’s worn and crumpled clothing would give things a fresh air that we hadn’t conceived of beforehand.” US news editors were also taken with the casual militarism of the insurgents and pursued a narrative that chimed with the emerging counterculture, nicknaming the rebels Castro’s barbudos (‘bearded ones’).

There was a growing awareness amongst those who disliked Cuban guerrillas that their image was capturing the popular imagination. When the British government declassified 1960 documents from the British embassy in Havana in 2004, they revealed concerns with Guevara’s involvement in the revolution and his government position.

The documents paint a vivid description of Guevara as a “bearded Argentinian, with his Irish charm and his inevitable military fatigue uniform, [who] has exercised considerable fascination.” Their focus on Guevara’s Irish heritage and dressed-down appearance is revealing and suggests this transnational figure for radical socialism embodied a new kind of threat to the establishment.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

From RTÉ Archives, Che Guevara talks to RTÉ News reporter Seán Egan during a stopover in Dublin in 1964 with Aer Lingus air hostess Felima Archer acting as interpreter

On the first day cover for the An Post stamp, a quote from Guevara’s father, Ernesto Guevara Lynch, reads “in my son’s veins flowed the blood of the Irish rebels,” but how significant is the Irish connection? We might dismiss such romantic allusions to Ireland’s history of revolution, but Guevara valued solidarity with various anti-imperialist struggles and went on to assist insurgents in the Congo and Bolivia.

At a time when images were circulating with increased velocity, style was not a trivial matter in conveying political struggles. The unusual birth and enduring appeal of the Heroic Guerrilla image suggests that style matters even in military conflict. The Argentinian with Irish ancestry who crafted a revolutionary image resonated with people in various regions, including Ireland. As Castro came to realise, having a “poster child for rebellion” can be an effective weapon in a media age.

Dr Jane Tynan is Assistant Professor of Design History and Theory in the Department of Arts and Culture, History and Antiquity at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ