Loving to Read; Resisting Totalitarian Regimes: A Spiritual Meditation – Patheos

I love to read, and perhaps you do too. Plus, I despise totalitarian dictatorships, and perhaps you do too. Is there any connection? Perhaps….

In a new book of essays on her reading adventures, titled Ex Libris, the long-time New York Times reviewer Michiko Kakutani mentions one of her favorites, A History of Reading (1996) by Alberto Manguel. In it, says Kakutani,

“Manguel described a tenth-century Persian potentate who reportedly traveled with his 117,000-book collection loaded on the backs of “four hundred camels trained to walk in alphabetical order.” Manguel also wrote about the public readers hired by Cuban cigar factories in the late nineteenth century to read aloud to workers. And about the father of one of his boyhood teachers, a scholar who knew many of the classics by heart and who volunteered to serve as a library for his fellow inmates at the Nazi concentration camp Sachsenhausen. He was able to recite entire passages aloud—much like the book lovers in Fahrenheit 451, who keep knowledge alive through their memorization of books.”

Imagine lugging your own collection of books (which probably numbers a lot less than 117,000) everywhere you go. And yet: those that we truly “own,” we do lug around with us. Imagine sitting in a factory all day, reading aloud to the bored workers as they roll cigars. Sometimes, we do memorize passages from our favorite books, as in the case of one friend of mine who is able to recite long sections of Scripture, savant-like. But imagine, as in Fahrenheit 451, being charged with memorizing an entire book of the Bible–and then being the lone surviving trustee of that material (which is famously burned in the story). Which “classics” do you know “by heart”?

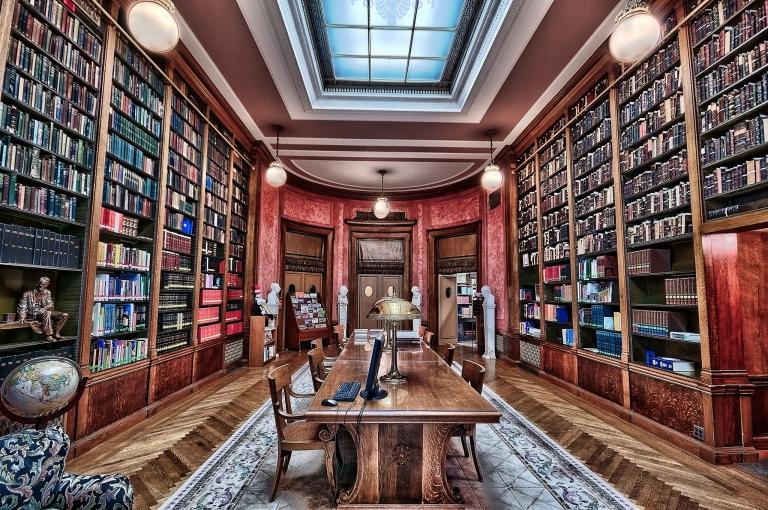

Kakutani is especially powerful in her alluring, often luscious descriptions of the reading life. She loves books, and wants you, dear reader, to love them as well. And so do I! Thus, my featured image for this column: a quiet, well-stocked private library as a sort of imaginative Garden of Eden of the mind. But what does this Edenic setting have to do with the real world of politics, 2020-style?

The context of these imaginative exercises is Kakutani’s lengthy discussion of one of her favorite books, Hannah Arendt’s 1951 classic, The Origins of Totalitarianism. Perhaps some may find this an oddly dissonant pairing of concepts. But in Kakutani’s universe, there’s a direct connection between the reading and writing life, the growing lack thereof in 2020 America, and then the emergence of bad leaders and governmental overreach. Here is how Kakutani ends her own meditation on Arendt’s book:

“The Origins of Totalitarianism is essential reading not only because it reminds us of the monstrous crimes committed by Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union in the twentieth century but also because it provides a chilling warning of the dynamics that could fuel totalitarian movements in the future. The book underscores how alienation, rootlessness, and economic uncertainty can make people susceptible to the lies and conspiracy theories dispensed by tyrants. It shows how the weaponization of bigotry and racism by demagogues fuels populist movements built upon tribal hatreds while undermining the longstanding institutions meant to protect our freedoms and the rule of law and shattering the very idea of a shared sense of humanity.”

Any of this sounding familiar? “The dynamics that could fuel totalitarian movements in the future”: check. “Alienation, rootlessness, and economic uncertainty”: check. “People susceptible to the lies and conspiracy theories dispensed by tyrants”: check. “Populist movements built upon tribal hatreds”: check. “Undermining the longstanding institutions “: check.

Checkmate? Not quite yet. Frankly, I dislike sounding like a prophet of doom; there’s enough of all that around, if you care to partake.

But let’s take this all as a cautionary tale of what might be plausible: the rise of some hideous power, despite our sense that it could never happen here in America.

As Kakutani reminds us, “two of the most monstrous regimes in human history came to power in the 20th century, and both were predicated upon the destruction of truth—upon the recognition that cynicism and weariness and fear can make people susceptible to the lies and false promises of leaders bent on unconditional power.” Cynicism and weariness and fear all sounds to me a lot like Covid-time 2020–especially the weariness.

Heading to the polls next week (although over 60 million have ALREADY voted this year): let’s keep our eye on the ball. It may sound silly to suggest that reading can save us. But Kakutani is right about one thing: reading wisely, and then parlaying our reading into useful evidence in our search for Higher Truth, are essential ingredients in the crock pot stew we call our freedoms and our democratic system–as Arendt has reminded us.

As a teacher of literature, it’s an empowering idea. The good news is, loving to read and hating totalitarian regimes go hand in hand: a premise I want to announce to the world, here and now, in my barbaric yawp! And perhaps you do, too.

image by Tom Finzel, Flickr