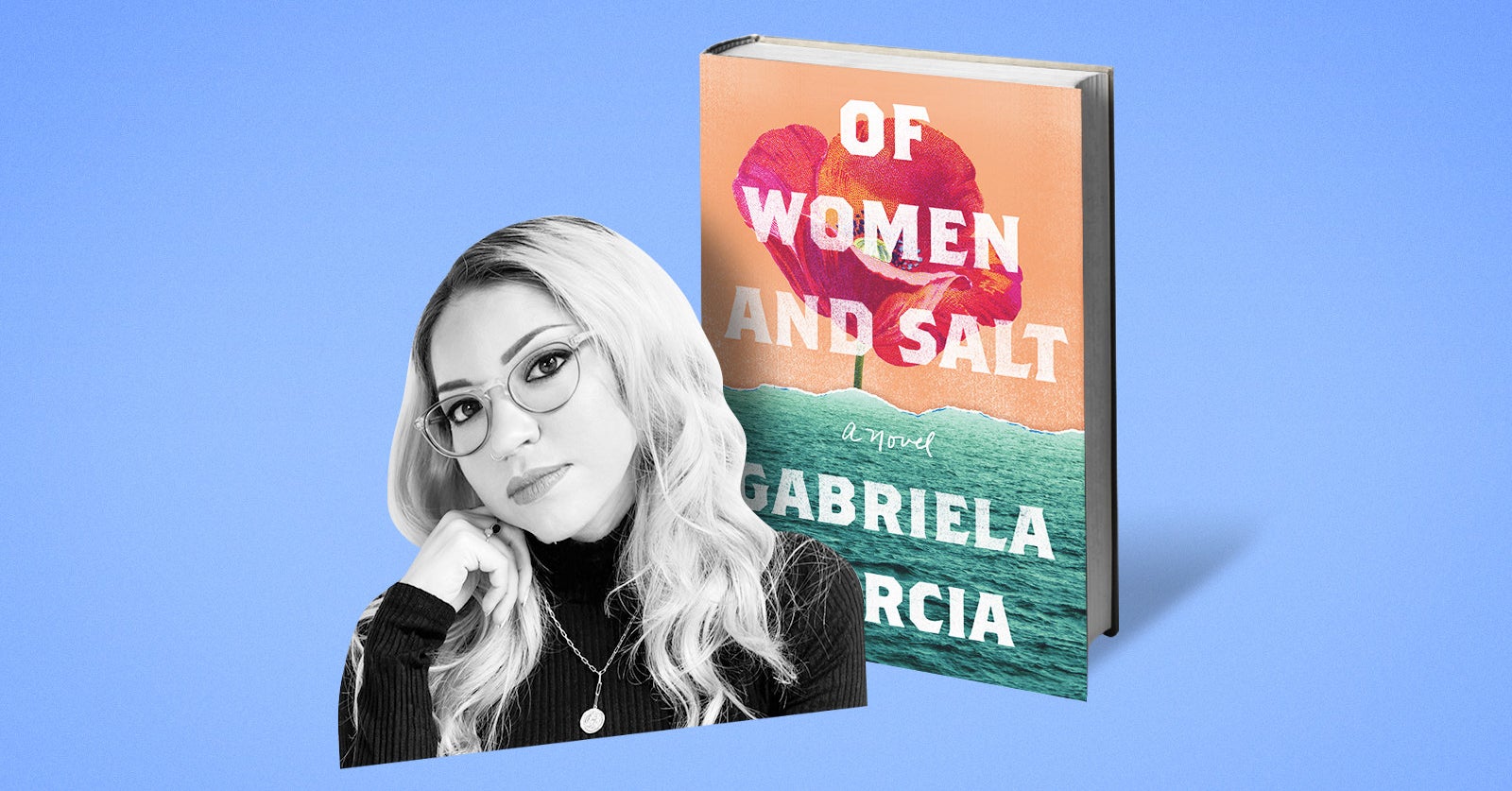

“Of Women And Salt” Is BuzzFeed Book Club’s April Pick. Here’s An Excerpt. – BuzzFeed News

To celebrate, we’re collaborating with Flatiron Books, Lucky No. Candles, and Libro.fm to give one lucky winner a signed copy, audiobook, and an 8 oz. candle that’s perfect for spring. Enter here!

Carmen

Miami, 2018

Jeanette, tell me that you want to live.

Yesterday I looked at photos of you as a child. Salt soaked, sand breaded, gap toothed and smiling at the edge of the ocean, my only daughter. A book in your hand because that’s what you wanted to do at the beach. Not play, not swim, not smash-run into waves. You wanted to sit in the shade and read.

Teenage you, spread like a starfish on the trampoline. Do you notice our crooked smile, how we share a mouth? Teenage you, Florida you, Grad Nite at Epcot, two feet in two different places. This is possible at Epcot, that Disney tiny-world, to stand with a border between your legs.

Sun child, hair permanently whisked by wind, you were happy once. I see it, looking over these photos. Such smiles. How was I to know you held such a secret? All I knew was that you smiled for a time, and then you didn’t.

Listen, I have secrets too. And if you’d stop killing yourself, if you’d get sober, maybe we could sit down. Maybe I could tell you. Maybe you’d understand why I made certain decisions, like fighting to keep our family together. Maybe there are forces neither of us examined. Maybe if I had a way of seeing all the past, all the paths, maybe I’d have some answer as to why: Why did our lives turn out this way?

You used to say, You refuse to talk about anything. You refuse to show emotion.

I blame myself because I know your whole life, you wanted more out of me. There is so much I kept from you, and there are so many ways I made myself hard on purpose. I thought I needed to be hard enough for both of us. You were always crumbling. You were always eroding. I thought, I need to be force.

I never said, All my life, I’ve been afraid. I stopped talking to my own mother. And I never told you the reason I came to this country, which is not the reason you think I came to this country. And I never said I thought if I didn’t name an emotion or a truth, I could will it to disappear. Will.

Tell me you want to live, and I’ll be anything you want me to be. But I can’t will enough life for both of us.

Tell me you want to live.

I was afraid to look back because then I would have seen what was coming. The before and the after like salt whipping into water until I can’t tell the difference, but I can taste it on your skin when I hold your fevered body every time you try to detox. Every story that knocked into ours. I was afraid to look back because then I would have seen what was coming.

María Isabel

Camagüey, 1866

At 6:30, when all the cigar rollers sat at their desks before their piles of leaves and the foreman rang the bell, María Isabel bent her head, traced a sign of the cross over her shoulders, and took the first leaf in her slender hands. The lector did the same from his platform over the workers, except in his hands he held not browned leaves but a folded newspaper.

“Gentlemen of the workshop,” he said, “we begin today with a letter of great import from the esteemed editors of La Aurora. These men of letters express a warm fondness for workers whose aspirations to such knowledge — science, literature, and moral principle — fuel Cuba’s progress.”

María Isabel ran her tongue along another leaf’s gummy underside, the earthy bitterness as familiar a taste by now as if it were born of her. She placed the softened leaf on the layers that preceded it, the long veins in a pile beside. Rollers, allowed as many cigars as they liked, struck matches and took fat puffs with hands tented over flames. The air thickened. María Isabel had by then breathed so much tobacco dust she developed regular nosebleeds, but the foreman didn’t permit workers to open the window slats more than a sliver — sunlight would dry the cigars. So she hid her cough. She was the only woman in the workshop. She didn’t want to appear weak.

The factory wasn’t large, by Cuban standards: only 100 or so workers, enough to roll for one plantation a mile away. A wooden silo at the center held its sun-dried leaves, darkened, papery slivers the rollers would carry to their stations. Next to the silo, a ladder flanked the chair where Antonio, the lector, sat.

He cleared his throat as he raised the newspaper. “La Aurora, Friday, first of June, 1866,” he began. “‘The order and good morals observed by our cigar makers in the workshops, and the enthusiasm for learning — are these not obvious proof that we are advancing?’”

María Isabel picked through her stack of leaves, setting aside those of lesser quality for filler.

“‘. . . Just go into a workshop that employs two hundred, and you will be astonished to observe the utmost order, you see that all are encouraged by a common goal: to fulfill their obligations . . .’”

Already a prickling warmth spread across María Isabel’s shoulders. The ache would grow into a throb as the hours passed so that, by the end of the workday, she could barely lift her head. To fulfill their obligations, to fulfill their obligations. Her hands moved of their own accord. The bell would ring and she’d look at the pile of cigars, smooth as clay, surprised she’d rolled them all. She imagined the layers of brown melding into one another endlessly — desks becoming walls, leaves becoming eyes, and sprouting arms moving in succession until everything and everyone were part of the same physical poetry, the same song made of sweat. Lunchtime. She was tired.

A single dirt road in this town led past the factory’s gate and continued on to the sugar plantation a mile down, both owned by a creole family, the Porteños. María Isabel walked this path home, one that snaked through the shadows and gave her brief reprieves from the punishing sun. She thought of Antonio’s words: Study has become a habit among them; today they leave behind the cockfight in order to read a newspaper or book; now they scorn the bullring; today it is the theater, the library, and the centers of good association where they are seen in constant attendance.

True that since La Aurora had expounded the uncivilized nature of cock-and bullfighting, the number of participants had diminished. But it wasn’t just the newspaper’s recommendation that convinced them to give up blood sport. There were also preoccupations. Other workers talked about rebel groups rising up against Spanish loyalists. About men training in groups to join others headed west toward La Habana. María Isabel had been too hardened by her father’s recent death, from a demonic yellow fever that consumed him within weeks, to notice at first, to care much. But then it was all anyone would talk about.

She hated the unknowing. She hated that her own survival depended on a shadowy political future she could hardly envision.

Though by the time rumors of guerrilla fighting had spread to their side of the island, so, too, had stories of infighting. Generals of the militias came and went, supplanted when their ideals became a liability. La Habana, with its manor after manor of Spanish families, looked toward the revolt with indifference, and it appeared more and more likely that the Queen would come down hard on any rebellion. For María Isabel, a scorching anxiety had long replaced those lofty early notions: freedom, liberty. She hated the unknowing. She hated that her own survival depended on a shadowy political future she could hardly envision.

Home. María Isabel’s mother sat on the ground, back against the cool mud of the bohío. Aurelia had returned from work herself, from the fields.

“Mamá?” María Isabel alarmed to find her in such a way, an unusual blush spreading up Aurelia’s face to the tips of her ears.

“Estoy bien,” she said. “Just faint from the walk. You know I am less and less capable.”

“That isn’t true.”

Aurelia steadied herself with one hand to the wall.

“Mamá.” María Isabel touched Aurelia’s forehead with the back of her hand, which gave off such a stench of tobacco juice that her mother winced. “Stay out in the breeze and rest in the hamaca, won’t you? I’ll prepare lunch.”

Aurelia patted María Isabel’s arm. “You are a good daughter,” she said.

They walked to a hammock knotted between palms.

María Isabel’s mother, worn down by decades of loss, hard toil, nonetheless retained a certain elegance. Her skin was smooth, with hardly a line, her teeth neat rows unstained. After her husband’s death, Aurelia had many callers, men with missing teeth and sun-weathered, papery skin who presented little in the way of wealth — a donkey, a small plot of mango and plantain trees — but offered care that she brushed off vehemently. “A woman does not abandon love of God, nor of country, nor of family,” she’d said in those days, before the men stopped seeking her out. “I will die a widow, such is my fate in life.”

But her mother grew weaker, María Isabel could see. Finding her daughter a suitable husband had become an aggressive devotion. María Isabel protested: She was happiest in the workshop, in the fields, sweating over fire, peeling yucas and plantains and tossing them into a cast-iron cazuela of boiling water with her sleeves bunched to her elbows, catching pig’s blood in a steel bucket to make shiny-black sausage, hacking open a water-pregnant coconut with two swings of a machete. True that cigar rolling was a coveted, respectable job — she’d apprenticed for nearly a year prior to working for a wage. Yet the factory paid her by the piece, half of what the men earned, and she was the only woman in the shop, knew the men resented her. They’d heard about this new invention, in La Habana — a mold that made it easy for almost anyone to roll a tight cigar — and feared María Isabel a harbinger of what would come: unskilled, loose women and grubby children taking their jobs for almost nothing. Suggested she might earn better keep “entertaining” the men herself. Took a greater share of her wages to pay the lector.

There were moments, like now, watching her mother lie red faced in the hammock through the window, when she pictured a world in which Aurelia wouldn’t have to work, in which she spent her time caring for her mother instead of rolling tobacco with the men. And she knew with resignation that she’d say yes to any man who offered easier days. Such was her fate. ●

From Of Women and Salt by Gabriela Garcia. Copyright (c) 2021 by the author and reprinted by permission of Flatiron Books.

Gabriela Garcia is the recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award and a Steinbeck fellowship from San Jose State University. Her fiction and poetry have appeared in Best American Poetry, Tin House, Zyzzyva, Iowa Review, and elsewhere. She received an MFA in fiction from Purdue and lives in the Bay Area. Of Women and Salt is her first novel.