The amazing tale of the 39-year-old rookie – MLB.com

You couldn’t make Conrado “Connie” Marrero stop pitching. That was true when he was a 27-year-old pitching for the first time in the amateur Cuban Leagues, that was true when he became a 39-year-old rookie with the Washington Senators in 1950, and that was true in 1999 when Marrero refused to leave the mound before the Orioles took on the Cuban National Team for a historic preseason exhibition.

That’s not a joke, either — in 1999, when the Orioles flew to Havana, Marrero was brought out to throw the ceremonial first pitch. Except, he didn’t throw one pitch, bow before the crowd and walk off. He threw another. And another. He didn’t give up until Brady Anderson finally gave a half-hearted swing.

As Marrero, who died in 2014, was quoted as saying on his 101st birthday, “I’m ready to pitch again, but I don’t have a catcher.”

—

The Beginning

Oddly enough, for someone so devoted to pitching, Marrero didn’t start that way. No, the ballplayer from Sagua La Grande, a small town on the north coast of Cuba, actually began his baseball life as a third baseman. He stopped after he said he “caught a bouncer in the face and lost some teeth.”

So, Marrero — and the stogie that seemed almost attached to his mouth — took to the mound for the first time 1938. He became an immediate success … at the age of 27. More players might retire than take up a whole different position that would span for decades later, but Marrero wasn’t most players.

“And then in ’38, he joins the amateur league and he becomes, overnight, the greatest pitcher,” Kit Krieger, a SABR member and owner of Cubaball tours, who became a close friend of Marrero’s, told MLB.com. “But he’s already 27 years old. To start pitching his first game at 27 … and still [be] a 350-game winner,” he exclaims as he trails off, pointing to Marrero’s career win total across multiple teams, leagues and countries.

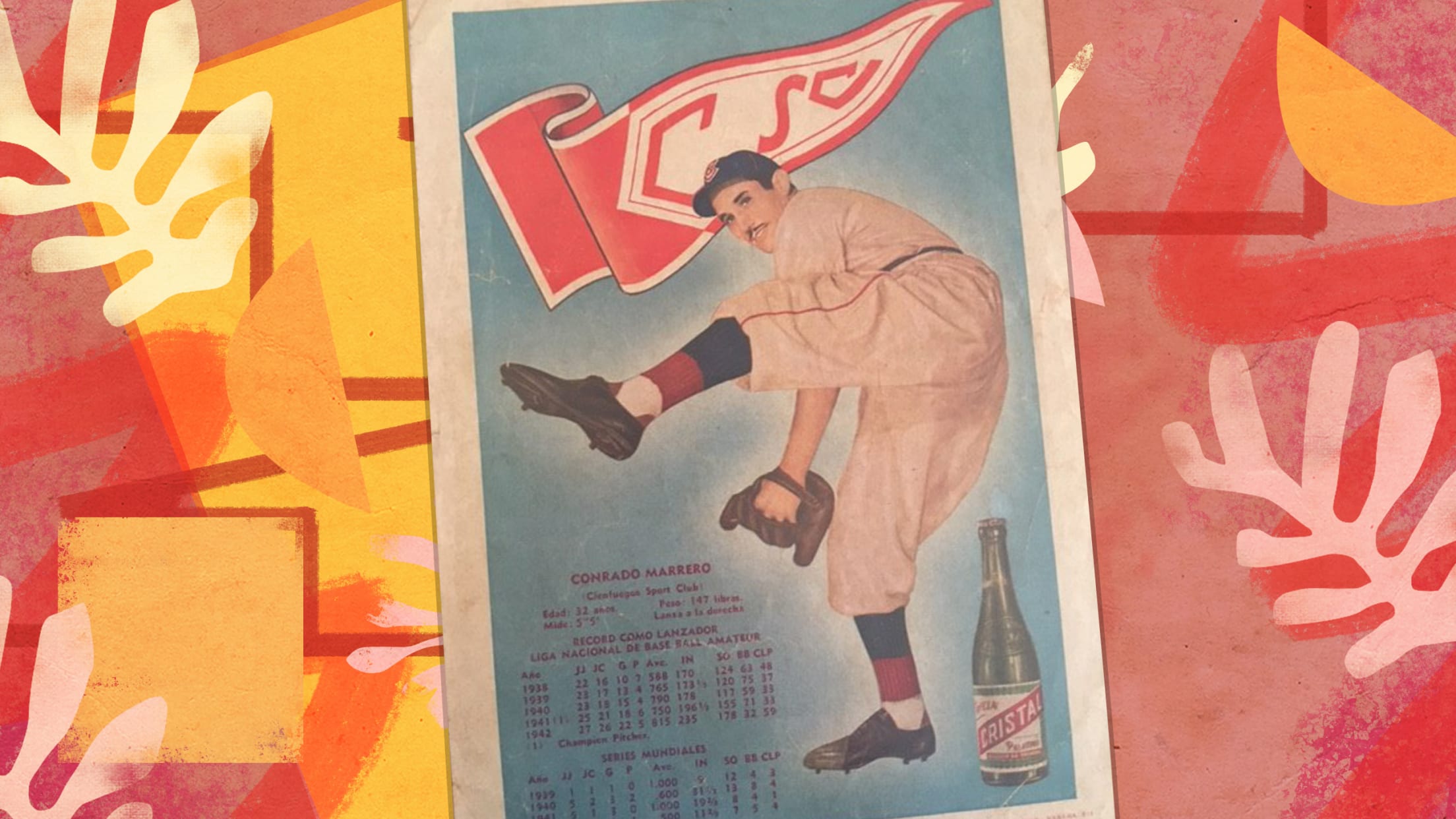

That first year, Marrero won 10 games with a 2.54 ERA. He only got better from there, culminating in 1942 when he went 22-5 with a 1.22 ERA for Cienfuegos, and received the most fan votes on the Cuban National Team. Fans flocked to the stadium when he pitched, and he led the Cuban National Team to three Amateur World Series titles.

Still, he wouldn’t turn pro until he was 35 years old after being caught playing for two teams in Cuba. It would take four more years until he made it to the Major Leagues. Like many aging players at the time, he did his best to obscure his age, lest it keep him from finding work. It’s rumored that Senators owner Clark Griffith believed he was eight years younger than listed. The Saturday Evening Post once wrote that Marrero was, “positively 35, absolutely 37, indisputably 43, and definitely 42.”

“He’s got more birthdays than Satchel Paige would ever dream of,” Krieger joked. “I’ve seen 1911, 1915, 1917, and May 1, April 23, and August-something.” (His birthdate is currently listed as April 25, 1911 — the date found on an old passport in Krieger’s collection.)

A 1943 ad with Marrero endorsing Cristal cervesa. Courtesy Kit Krieger’s collection.

The Stories

Still, there aren’t many big leaguers who make their debut at 39. In fact, Marrero is the 11th-oldest rookie pitcher in history. At the time he played, he was just the eighth.

Scouts today might not even look at him given his size. He was listed at just 5-foot-5 and 158 lbs, making him the third-shortest pitcher in the modern era. Quite frankly, everything about him says he shouldn’t have made it to the Major Leagues — and yet he did.

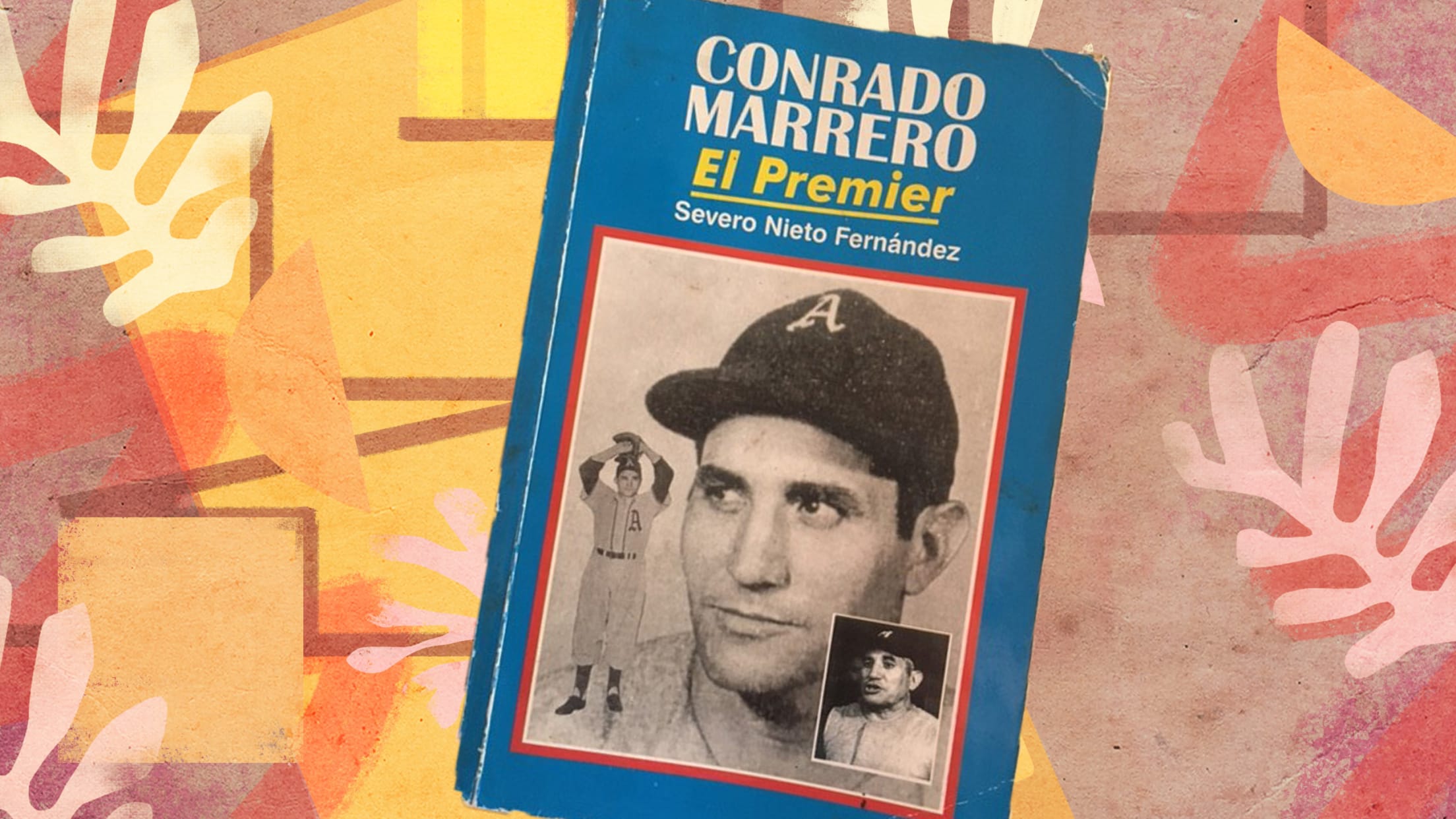

He earned several colorful sobriquets for his loping wind-up and looping curveball. In Cuba, he was known as El Premier (“Number One”), El Curveador (“The Curveballer”) and El Guajiro (“The Hillbilly”) for his farmland roots, where he learned to pitch by throwing oranges at tree trunks. Sadly, those impressive nicknames didn’t cross over to the big leagues, where he was known as Connie, or, “a muscle-bound little gnome.”

Felipe Alou called his delivery “a cross between a windmill gone berserk and a mallard duck trying to fly backwards.”

His career was seemingly made for colorful descriptions — something that Marrero certainly didn’t seem to mind. Sure, he was known for his curveball, but he had every pitch under the sun in his arsenal. He once reportedly claimed through an interpreter that he threw, “Everything but my cigar.”

Severo Nieto Fernández’s biography of Marrero. Courtesy Kit Krieger’s collection.

Blessed with some perfect pitches and a pitch-perfect memory for almost every batter he ever faced, he recalled how he managed to strike out Ted Williams. After getting The Splendid Splinter to foul off two sliders, Marrero uncorked a floating knuckleball to get the Hall of Famer to strike out.

“Theodore hates the knuckleball . . . and the slider,” Marrero said. “But he learned to hit them, anyway.”

Of course, this is one of the greatest hitters of all-time, so Williams got his revenge. As Marrero told Thomas Boswell in the Washington Post in 1978:

“In Boston, he hit two home runs off me in one game. One slider. One knuckleball. After the game, he put his arm around me under the stands and said, ‘This was my day.’

“I told Williams,” said Marrero, “every day is your day.” (This was true more often than not in their meetings: Williams pasted Marrero to the tune of a career batting line of .333/.450/.697 in 40 PA.)

Ted Williams faces the Senators in 1954.

Eddie Robinson, who recently turned 100 years old, was both a teammate and opponent of Marrero’s and remembers him well. “He liked the big cigar. He had the big leg kick. And he was a pretty good pitcher,” Robinson told MLB.com, comparing him to another celebrated junkballer, Eddie Lopat.

After getting traded from the Senators to the White Sox, the two faced off regularly, with Marrero holding the slugging Robinson to just a .175 average.

“After I got traded to Chicago,” Robinson said, “then I had to hit him, and he was pretty damn tough on me. He got me out pretty easy.”

Marrero apparently had some insight into that. The pitcher had recounted a story when he was 102 about a batter he was about to face with the last name Robinson. Senators manager Bucky Harris came out to suggest they pitch him up and in, but Marrero cautioned that if he did that the outfielders should be ready for a “big hit.” Instead, he suggested they pitch Robinson low and away with breaking stuff.

The two argued, with Marrero eventually offering a wager:

“I bet a cigar that, like this, I can get him out!” Marrero said.

“I accept!” Harris said.

Sure enough, Marrero got the batter to pop out, earning the victory stogie. Could this Robinson — one of only two that Marrero faced in his career — be Eddie? Robinson confirmed with a chuckle that yeah, it probably was.

—

The Workhorse

Marrero’s big league career was short — because of course it was when he started around the time people have their mid-life crisis. Playing for the cellar-dwelling Senators certainly didn’t help much.

He put up solid numbers, though, going 39-40 with a 3.67 career ERA. Those numbers were good enough to earn him a trip to the All-Star Game in 1951, when he set a then-record as the oldest first-time All-Star that was later broken by Satchel Paige. He’s still one of just four players, including Jamie Moyer and Tim Wakefield, to make their first trip to the mid-summer jewel in their ’40s.

But who knows how much better he could have been on a better team, or how much fame the quotable, cigar-chomping pitcher could have come his way if he ever got to pitch in the postseason?

Of course, maybe he could have been better — for Marrero never stopped pitching. He spent his winters pitching in Cuba, so he reportedly would lose his effectiveness later in the season as fatigue caught up with him because he kept throwing while “other hurlers are resting their aching bones.”

One example comes from 1947 when, between pitching in Mexico and Washington’s C-League team, Marrero combined to go 37-8 and pitch 451 innings.

Krieger asked him how such a thing was even possible. “But he just didn’t understand the question,” Krieger said. “His mechanics must have been perfect.”

Still, age catches up to even those with smooth mechanics and ligaments blessed by the gods, and after struggling in 1954 and being moved to the bullpen, the Senators released Marrero.

Marrero next pitched for the Reds’ farm club in Havana until 1957. He then pitched in Nicaragua, piling up more innings and certainly more victories, though the stats are lost, before becoming a Red Sox scout. All told, he went 353-173, with 88 shutouts. Not bad numbers for a late bloomer.

—

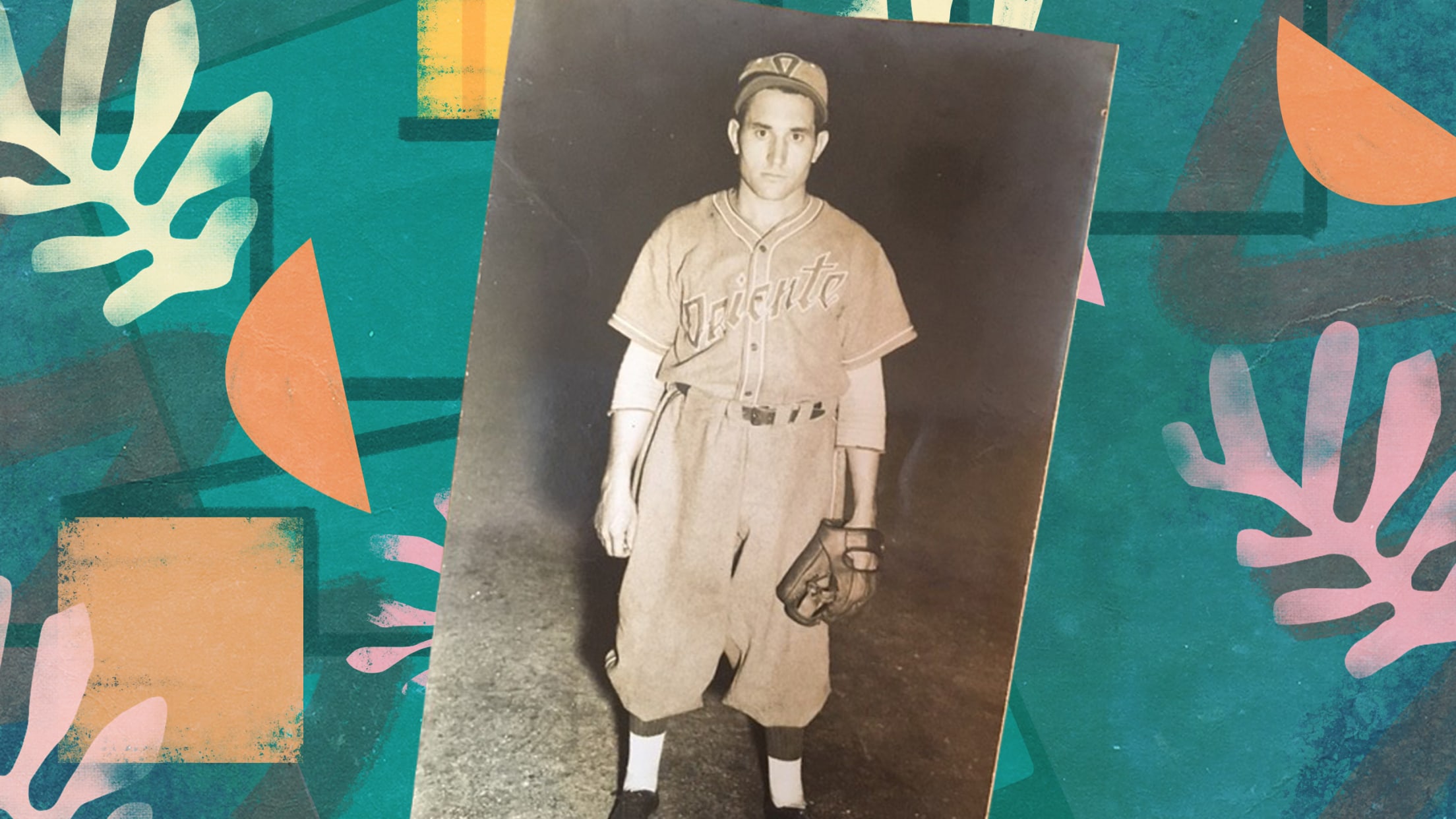

Marrero in 1946 or ’47 with Oriente in the Cuban winter league. Courtesy Kit Krieger’s collection.

The Centenarian

Following the Cuban revolution, Marrero stayed in the country and became a legend at home. He helped develop pitchers and impart wisdom from his decades-long baseball career. Still, not everything went to plan.

Years later, when Krieger first met Marrero, he found the old man living in a small apartment with his grandson and living off just a $7 pension per month. With the help of his fellow Cuban baseball enthusiasts, Krieger helped send Marrero money to live on, but it wasn’t enough. Krieger quickly got to work — first collecting letters from Marrero’s old teammates and opponents who fondly remembered him, letting “El Premier” know they didn’t forget him.

Krieger then contacted MLB, the Association of Professional Baseball Players of America, and BAT (Baseball Assistance Team) for help. He got in touch with Robinson, who called up former New York Daily News writer Bill Madden to find any relief that could be sent to Marrero, who wasn’t initially eligible for a pension because he had opted out during his playing career.

But it wasn’t just a struggle to get the funds, they also had to find a way to get the money to Marrero. Because of the strained relations between the U.S. and Cuba, they couldn’t just wire some cash to Marrero.

So, like some kind of spy movie, they discovered a loophole: With former big leaguer Stan Javier living in the Dominican Republic, he could enter Cuba and deliver checks to Marrero. So, for the last four years of his life, Marrero earned $10,000 a year from baseball — “that was a big difference, a tremendous difference,” Krieger said.

When asked how he became so close to Marrero and why the old ballplayer became such an important person to him, Krieger answered simply. “What’s better for me than to sit in the living room of a guy and talk about DiMaggio and Mantle and Bucky Harris — who he called Bucky Harry,” Krieger said, before launching into a tale about how Marrero never could get Larry Doby out.

Marrero passed away in 2014, just a few days shy of his 103rd birthday and a planned national celebration of his life in baseball. For the man who seemingly couldn’t forget a moment from his baseball journey, in the end, he wasn’t forgotten by it, either.

Michael Clair writes for MLB.com. He spends a lot of time thinking about walk-up music and believes stirrup socks are an integral part of every formal outfit.