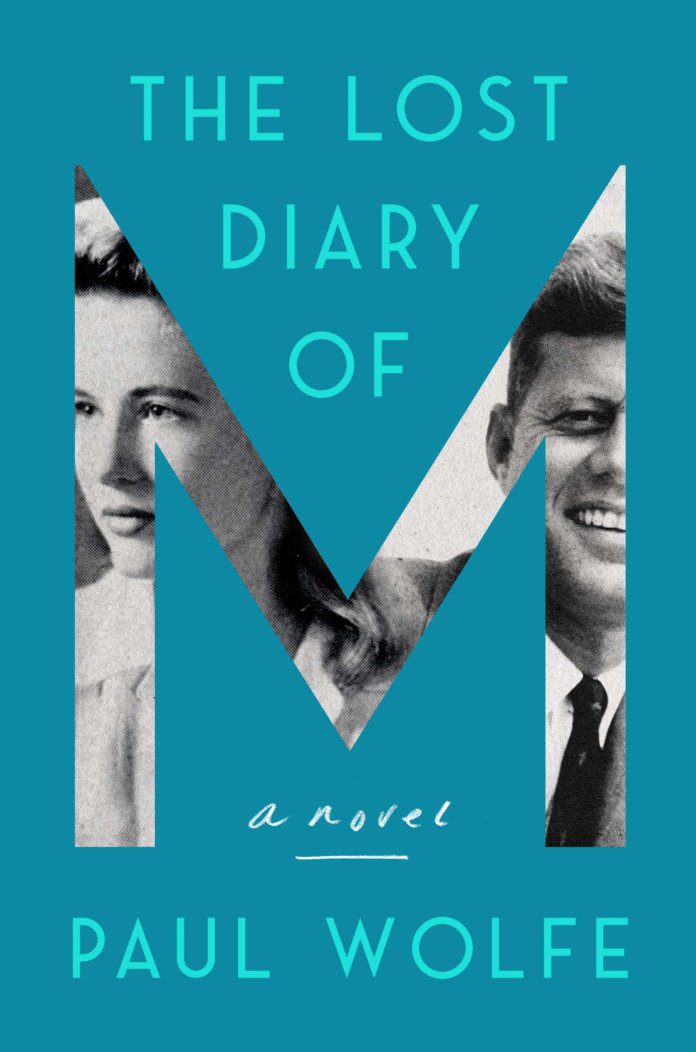

‘The Lost Diary of M: A Novel’ – Georgetowner

THIS FICTIONALIZED ACCOUNT OF ONE OF JFK’S REAL-LIFE LOVERS WILL DELIGHT CAMELOT BUFFS AND GOSSIP HOUNDS ALIKE

Many intriguing stories spring from the “what if ” crevices of a writer’s imagination to conjoin fact and fiction, which is how Paul Wolfe came to write his second novel, “The Lost Diary of M.”

“M” refers to CIA operative Cord Meyer’s ex-wife, Mary Pinchot Meyer, who had an affair with John F. Kennedy in the White House. Months after the president’s assassination, she was mysteriously murdered in broad daylight while walking along the C&O Canal in Georgetown. The accused assailant was found not guilty.

“The lost diary” refers to Pinchot Meyer’s journal, found after her death by her sister, Antoinette “Tony” Bradlee, then married to Ben Bradlee, who later became executive editor of the Washington Post. After she turned her sister’s journal over to their friend James Jesus Angleton, the CIA’s chief of counterintelligence, the diary was never seen again, nor its contents ever revealed.

Given those established facts and a cast of real characters, Wolfe takes off in the voice of Pinchot Meyer, who, according to public record, was an LSD disciple of Timothy Leary who shared drugs with JFK. Enter here the fictional fantasies of “what if.”

What if her diary was not destroyed? What if it reveals her life as an ex-CIA wife (“I learned the secrets of codes and agents and networks and interrogations”)? What if her diary contains all that JFK confided about the Bay of Pigs fiasco and the Cuban Missile Crisis? What if she discovers the CIA plot to assassinate Kennedy and refers to the Warren Commission and its lone-gunman finding as “Fictions from an Assassination”?

What if she storms a society ball in Washington and boldly confronts her former husband with evidence of his agency’s perfidy? What if that revelation eventually leads to her killing? What if her diary reveals her preposterous plan for world peace by having her circle of Georgetown wives give their powerful husbands LSD to lead them to “cellular evolution,” which moves them to see the folly of their power-seeking ways and — voila! — they end the Cold War?

(I use the word “preposterous” for this fictional fantasy, which Wolfe labels “Chantilly Lace,” but it’s probably no less harebrained than the actual CIA plan to assassinate Fidel Castro with an exploding cigar and, failing that, poison pills hidden in a cold cream jar.)

The challenge in writing a novel based on real people and events is making the nonfiction details so accurate that readers will accept the creative leaps. For the most part, Wolfe succeeds. One glaring exception, however, occurs when he has JFK say to Pinchot Meyer that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” That iconic phrase belonged to Martin Luther King Jr. Its placement in the novel is particularly jarring when the narrator tells readers: “Then he asks me to bend toward justice and nudges the back of my neck.”

Wolfe weaves his facts and fictions so tightly, you might need Google to see if John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower’s secretary of state, and his brother, CIA Director Allen Dulles, really did have “intimate business dealings with Hitler’s pals.” (They did.)

Did the British spy Kim Philby defect to the Soviet Union because he had a German mistress there, whom he later married? (He did.) Was there really an Operation Midnight Climax run by the CIA that financed bordellos and sent drug-addicted prostitutes to pick up men late at night, bring them back and ply them with LSD-laced drinks so that agents watching behind a hidden screen could monitor the drug’s effects? (There was — and they did.)

Having hoovered the JFK oeuvre, which, according to Wikipedia, now numbers between 1,000 and 2,000 books, Wolfe illuminates his characters with telling details: Kennedy’s “back brace,” Mary’s “unshaven arm pits.” He nails columnist Joe Alsop (Joseph Wright Alsop V) as an effete snob who refuses to dine in a Paris restaurant if the wine cellar is too close to the Metro, maintaining that the train’s vibrations disturb the sediment in the bottles.

Wolfe writes with grace and many of his sentences sparkle: “The words of Ted Sorenson, the devout Unitarian, the megaphone of Jack’s mind, a poet of politics.” Much of “The Lost Diary of M” will ring true to those who followed the comet of Camelot or lived in Washington when J. Edgar Hoover ran the FBI and sent his agents out to be hired as waiters and bartenders to listen for gossip. One hostess confides: “The best pastry chef I ever employed turned out to be an FBI agent.” Seems comical in the age of AI, when Alexa outperforms Mata Hari, but that was the ’60s.

Kennedy aficionados and conspiracy theorists will enjoy a thumping good read and appreciate Wolfe’s prodigious research. Journalists may note with interest his mention of Ben Bradlee in the author’s note, and how he questions Bradlee’s “tortuous half-century of conflicting and contradictory narratives about his ex-sister-in-law, Mary Pinchot Meyer, and his denials of his own CIA affiliations.”

What if … this is a clue to Wolfe’s next novel?

What if … Wolfe writes about a revered newspaper editor with agency connections who is driven to… What if?

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.” She serves on the board of Reading Is Fundamental, the nation’s largest children’s literacy nonprofit